Freedom of Religion: What Does the First Amendment Mean? Pt. 1

In this two-part essay, Cayden Connally explores the differing interpretations of the First Amendment to the Constitution. This first part will examine the historical context of the First Amendment. Part 2 will explore the common law precedent. A complete works cited will be published with the second installment.

The Case for the Accommodationist View of the Establishment Clause of the 1st Amendment - Part 1

Accommodationism, Strict Separationism, and the 1st Amendment

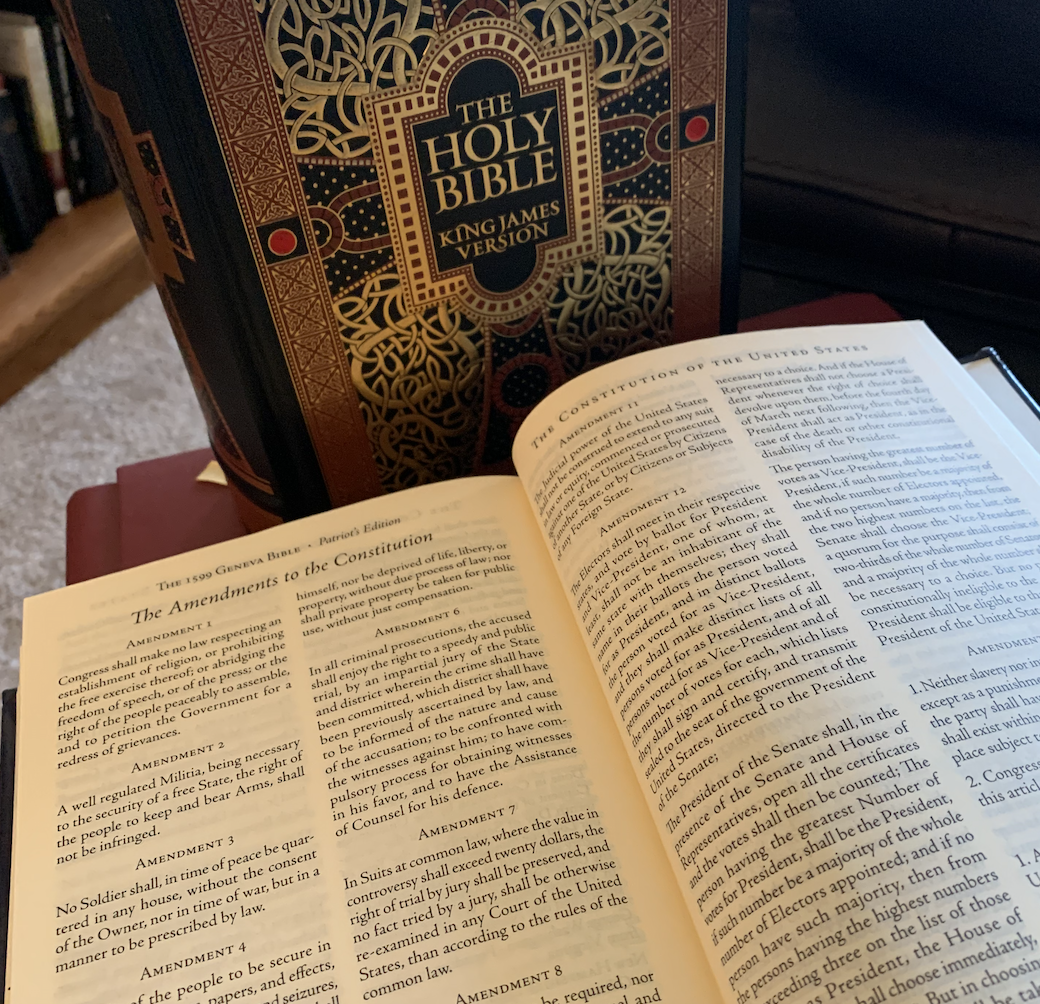

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…” Ever since they were ratified, these immortal opening words of the 1st Amendment have been the subject of heated controversy over the place of religion in the United States. What does it mean for a law to respect an establishment of religion? Does this mean that school prayer is unconstitutional? What about the display of religious symbols on public land? These are just some of the questions that have arisen over the proper interpretation of these Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the 1st Amendment, and two main schools of thought have emerged in constitutional law concerning the proper answers to these questions.

These two schools of thought are loosely known as “strict separationism” and “accommodationism” (Bopic). Strict separationists argue that the 1st Amendment was meant to completely keep religion outside the purview of government and that any law encouraging religion is unconstitutional (Bopic). Like Justice Hugo Black in the landmark Supreme Court decision, Everson v. Board of Education (1947), they argue that the 1st Amendment creates a “high and impregnable wall of separation” between church and state (Bopic). On the other hand, accommodationists argue that the 1st Amendment knows no such wall of separation and allows the government to promote religion (Bopic). Following Justice William Rehnquist’s dissent in Wallace v. Jaffree (1985), accommodationists contend that the intention of the 1st Amendment was to prohibit the government from instituting a national religion or preferring one religion over others (Vile, “Nonpreferentialism”).

Between these two schools of thought, the accommodationists have on their side the historical context of the Establishment Clause of the 1st Amendment. The accommodationists also have on their side the history of the common law precedent following the ratification of the 1st Amendment. From these facts, it is clear history demonstrates that the original intention of the Establishment Clause was more in line with accommodationism rather than strict separationism and that accommodationism is a more consistent standard than strict separationism.

Accommodationism and the Historical Context of the Establishment Clause

The historical context of the drafting of the 1st Amendment supports the notion that the Founders never intended what strict separationists mean by a “wall of separation.” On the contrary, the actions of the Founding Fathers exhibit the inherent religiosity of America’s institutions and consequently weigh in favor of the accommodationist interpretation of the Establishment Clause. Since the pilgrims first crossed the Atlantic, the words of Justice William Douglas have been true: “We are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being (Shultz 144).”

Though early colonial America was partially born out of concerns for religious freedom, that did not prevent the colonies and soon-to-be states from creating individual established religions of their own (Vile, “Established Churches in Early America”). For instance, Congregationalism enjoyed state sponsorship under Puritan influence in the New England colonies, while the Church of England (the Episcopal Church after the American Revolution) was established in the Southern colonies (Vile, “Established Churches in Early America”). Even the adoption of the 1st Amendment and the Establishment Clause in 1791 did not lead to the destruction of established state churches (Vile, “Established Churches in Early America”). The New England states of New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Massachusetts did not officially eliminate their state religions until 1817, 1818, and 1833 respectively (Vile, “Established Churches in Early America”). This was because the wording of the Establishment Clause originally only prohibited the federal government from establishing a religion, hence the phrase, “Congress shall make no law…” (emphasis added). So, the original intention of the Establishment Clause had no problem against state governments accommodating religion if they chose to, but what about the federal government? While the issue becomes more complicated, the historical evidence still weighs in favor of accommodation.

In 1791 when the 1st Amendment was first drafted, the newly formed United States had just separated itself from Great Britain, which had the Anglican Church as its official established religion. So, given the previously mentioned religious character and diversity among the states, the Framers had an immediate interest in preventing a national establishment of a particular religion like the Episcopal Church, not in barring Congress from passing any law supporting religion in general. To do the latter would be to actively work against the common good of the generally religious people of the United States at the time.

This accommodationist interpretation is confirmed by the actions of Founding Fathers and personal friends from Virginia: Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the latter of whom would go on to draft the Bill of Rights. In 1784, one year after the formal end of the American Revolution, the legislature of Virginia considered a bill on whether or not to renew the state tax implemented to maintain the established Anglican Church (Baker). Working with dissenting Baptists, Presbyterians, and Quakers, Madison and Jefferson fought to disestablish the Anglican Church in Virginia by killing the tax and later adopting the “Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom” in 1786 (Baker; Ryman and Alcorn). So, it appears that Jefferson and Madison were friends of religious liberty, and Madison would later take up these sentiments again when drafting the Bill of Rights.

Taken in isolation, these actions of disestablishing the Anglican Church in Virginia may seem to paint Jefferson and Madison in a light favoring the strict separationist view. However, their actions on the federal level refute that contention. When Madison first gave his proposals for the first 10 Amendments in 1789, the first of the proposed Amendments was on the relationship between church and state and the precursor to the 1st Amendment (Deverich 217-218). This draft version read, “The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext, infringed (Deverich 218).” This indicates that Madison’s original idea for the relationship between the federal government and religion was to prevent the former from establishing a particular established institution of the latter, like the Anglican Church had been in Great Britain (Deverich 218). Consequently, Madison, the Father of the Bill of Rights himself, likely held to the accommodationist interpretation of the Establishment Clause.

Yet Madison’s draft was of course amended into its less clear present state, leaving some room for further doubt. Moreover, it would be remiss not to mention Jefferson’s famous “Letter to the Danbury Baptist Association,” written in 1802 and purported by strict separationists to give Jefferson’s—and consequently likely Madison and the other Founding Fathers’—interpretation of the Establishment Clause (Deverich 219-220). Jefferson says in the letter, “…I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between Church & State (Deverich 219-220).” This is what Justice Hugo Black quoted from in Everson and the greatest evidence other strict separationists have to support their view of the Establishment Clause. Nevertheless, the other actions of Jefferson and Madison as well acts of other portions of the federal government show that this “wall of separation” is not as strict as the separationists contend.

During their respective Presidential administrations, Jefferson and Madison each took actions that contradict strict separationists’ interpretation of Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptists (Ryman and Alcorn). Jefferson used his Presidential powers to approve treaties that sent missionaries to the American Indians (Ryman and Alcorn). Moreover, ever the respecter of the rights of states in addition to religious liberty, Jefferson said in his second inaugural address that religion “must then rest with States, as far as it can be in any human authority (Baker).” After Jefferson’s Presidency, Madison used his Presidential powers to proclaim periods of fasting and thanksgiving, like Washington before him (Ryman and Alcorn; The Writings of George Washington: from the Original Manuscript Sources). These actions from the Presidents concerning religion hardly seem consistent with the strict separationist interpretation of Jefferson’s letter and the Establishment Clause. Rather, the actions of Madison and Jefferson are much more consistent with the accommodationist interpretation, indicating that was the original intention of the Establishment Clause.

Accommodationism is also more consistent than separationism when it comes to other early actions taken by the federal government concerning religion. The same Congress that Madison proposed the 1st Amendment to also appointed a chaplain and convened the assembly with prayer (Noll and Harlow 82). In keeping with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787’s encouragement of religion, the federal government under the new Constitution and Bill of Rights also encouraged supporting religion in the western territories (Noll and Harlow 82). The federal government also used religious material provided by different denominations in order to help craft policy towards the American Indians (Noll and Harlow 82). Since its first session, the Supreme Court has opened with the cry, “God save the United States and this honorable court (Ryman and Alcorn).” This cry along with Congressional prayer and other similar traditions continue down to the present day, much to the consternation of strict separationists. Therefore, all this goes to show that the historical context of the 1st Amendment’s Establishment Clause weighs against the strict separationist view and in favor of the accommodationist view. Moreover, the history of the common law precedent on the Establishment Clause also weighs in favor of accommodationism in that it is a more consistent standard than strict separationism.

Cayden Connally is presently a senior at the University of Texas at Austin. He grew up in the West Texas town of Midland. Majoring in government and minoring in philosophy of law, his interests include learning about theology, philosophy, history, politics and how all these things play into one another. Moreover, he also enjoys watching classic films, visiting landmarks, and having deep discussions with friends. After graduating, Cayden plans to work in politics before eventually attending law school.